- Labour of Love

- Posts

- Selling the Workplace: On 'Mythic Quest'

Selling the Workplace: On 'Mythic Quest'

Mayanne investigates 'Mythic Quest' and its relationship to Ubisoft, television as a brand exercise, and soft propaganda.

Mythic Quest (2020-2025)

You know the feeling when a beloved show’s finale disappoints you so badly that you start wondering if you ever loved the show to begin with? Well, this has happened to me—more than once!—and the latest offender was the fourth and final season of Mythic Quest.

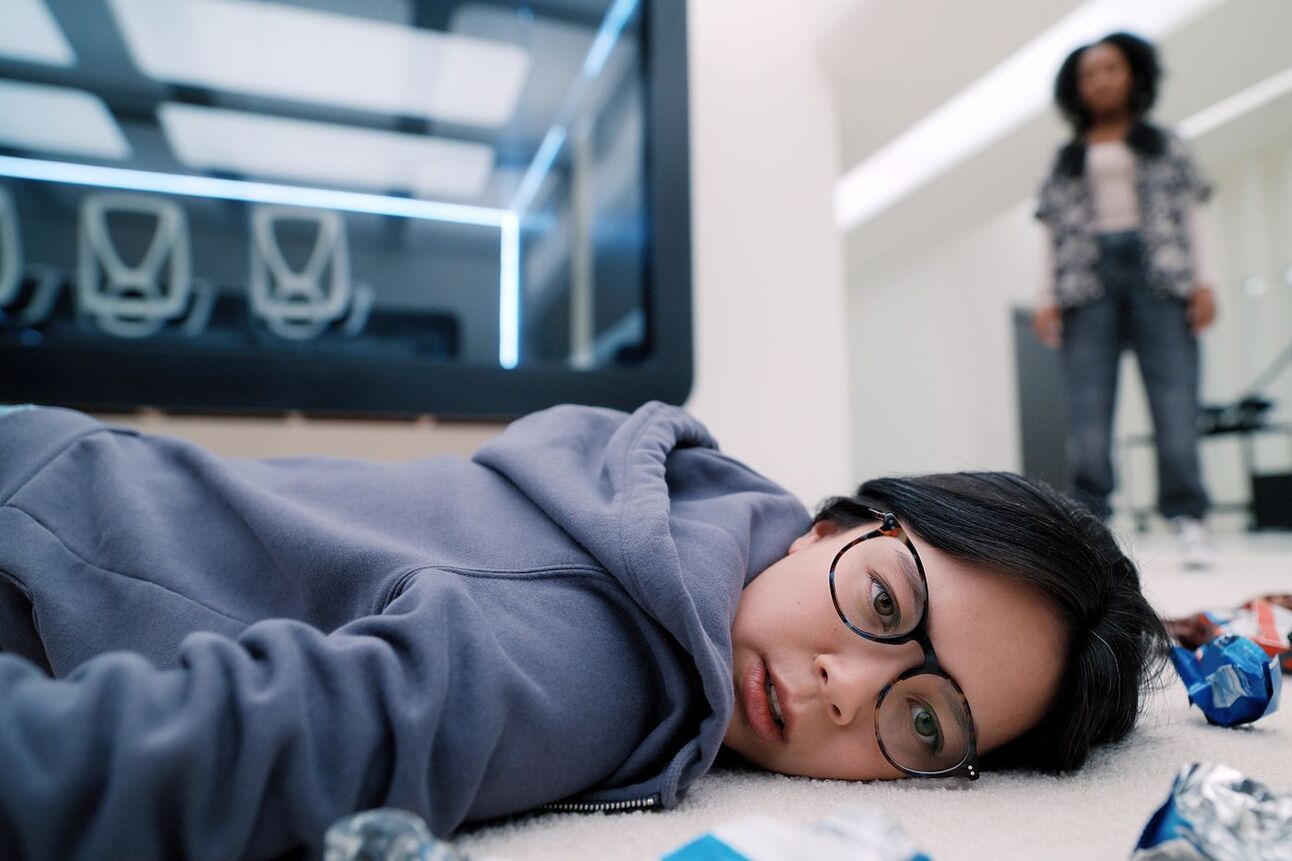

Mythic Quest is a workplace comedy set in the offices of a fictional video game company which oversees the development of a fantasy Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Game (MMORPG) of the same name. The show centres on the company’s leadership team along a few more junior employees, as they work on the Mythic Quest (MQ) universe, create spin-off games, and climb the corporate ladder. As far as workplace comedies go, this is a pretty fun watch, and after discovering it midway through season two in 2021, I happily came back to it season after season.

Mythic Quest’s strength is undeniably in its ensemble cast, not one of whom is out of place or underused, and it hits all the right notes when its humour focuses on its characters’ dynamics and individual quirks—from the incessant bad puns of MQ’s Lead Engineer and later Co-Creative Director Poppy (Charlotte Nicdao), to the insane tech bro vanity of her partner and MQ’s creator and Creative Director Ian (Rob McElhenney), and the unhinged ambition of Jo (Jessie Ennis), the Executive Assistant to the company’s insecure Executive Producer, David (David Hornsby). One of my favourite jokes, and a strong example of the show’s humour, comes when MQ’s Head of Monetisation, Brad (Danny Pudi), dramatically references Ducktales—a show Pudi is famously on—pointing to an animated character as his money-making role model. It is delightfully meta, a wink at Pudi’s work and humour off screen, and aligns perfectly with Brad’s in-universe characterisation as the team’s cartoonish capitalist evil genius. But like many workplace comedies, Mythic Quest has to contend with the politics of the industry it is set in, and this is where it ultimately fails.

Across its first three seasons, the show sometimes struggled when tackling structural issues at the core of the game industry—such as creatives’ work being dismissed and exploited by management, or the glamourisation of long, unpaid overtime, known in the industry as crunch. But these jokes were still marginal in number, and the show maintained a good balance of humour, wholesomeness and thoughtful storylines that kept me coming back. In season four, however, the poorly executed game industry jokes became inescapable, and the great ensemble moments that had made me fall in love with the show became rarer. Game Designer Dana (Imani Hakim), who is behind the company’s new hit game Playpen, a coding game for kids, is trapped in an exploitative contract which allows the company to claim ownership of any intellectual property she produces while employed by them, effectively letting them steal the next game she has been working on. David jokes about how profitable COVID was for the video game industry, brushing off the material impact it had on its workers and the millions of deaths lost to the virus. Poppy, who we have seen growing slowly unsatisfied and creatively limited by her role at Mythic Quest across the series’ four seasons, becomes pregnant and decides to move abroad to be with her boyfriend for the first year of their child’s life, only to change her mind and return to work because Ian doesn’t know his own passwords. These are serious issues—exploitative work contracts, a deadly pandemic, overworked employees, and men weaponizing incompetence to continue benefiting from women’s labour—that the show vaguely gestures at before moving on swiftly, never actually building an interesting commentary.

For me, the worst of joke of the season came early on in episode two, ‘1000%,’ when the show attempted to tackle AI’s creeping presence in the workplace, the tech industry’s exploitation of Global South workers, and the mental health crisis of online content moderators, all at once, without actually saying anything about any of these issues. In the episode, we see the team struggle with how to moderate their latest product, Playpen, a coding game for kids which is seeing an increase in user-generated sexually explicit content. Up until that point, moderation was handled by a single employee, the always cheerful Sue (Caitlin McGee), who works by herself from the company’s windowless basement. Between seasons three and four, it's implied that her ‘department’ has been expanded to one other employee and a team of outsourced moderators in India (undoubtedly hired as external contractors with low pay and no workers protection). When the team mentions using Mythic Quest’s new AI model to moderate the game, instead of the human workers it employs, Poppy—the model’s creator—warns that it is not robust enough for the task. She is promptly ignored, as MQ launches the AI and fires all contractors and extra employees, leaving Sue alone once again. While I guess this was an attempt at addressing the tech industry's use of underpaid, outsourced moderators in the Global South, which is exposing already vulnerable workers to distressing content with no support, it is an incredibly clumsy one at best, if not entirely insincere. The scene where David breaks the news to Sue that she will have to dismiss her entire department and go back to working on her own is given barely a minute of airtime, brushing over the impact of management’s decision, which will likely leave Sue to deal with an even greater workload as a result of an inadequate AI model being launched before it is ready. This is a very upsetting situation, yet the joke setup feels like it is mocking Sue’s distress rather than making a commentary on managements’ cluelessness and disregard for their own employees’ wellbeing.

This moment is key to understanding my growing frustration with the show: Mythic Quest uses humour to tackle serious issues, not to bring them to light or provide needed criticism, but to divert attention from them. They use a kind of cynical self-awareness that allows them to divest responsibility from the topics at hand, to condemn themselves just enough before the audience can, so that no further criticism can be leveraged at them. This, I would argue, is due to a conflict of interest at the heart of the show’s creation: in reality, Mythic Quest is not a show about the game industry more than it is shown by the game industry. As such, it cannot commit to a criticism that would effectively bite the hand that fed it.

To better understand this, we need to go back to the context of the show’s creation. Mythic Quest ran on Apple TV from 2020 to 2025. It was created by It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia’s Charlie Day, Megan Ganz and Rob McElhenney, and was produced by RCG Productions (It’s Always Sunny’s own production company), Lionsgate and… Ubisoft Film & Television. In fact, it was Ubisoft who initiated the idea of Mythic Quest, which was then picked up by RCG Productions.1 For those who are neither French nor video game players, Ubisoft is one of the world’s largest video game companies, with current annual revenues estimated at over 2 billion USD.2 Ubisoft Film & Television, created in 2011, is the company’s in-house production company, and handles screen adaptations of its most popular games, including Assassin’s Creed (2016), Werewolves Within (2021), and Rabbids Invasion (2013-2022). Mythic Quest is the company’s first live action series and is its first cinematic product to not be based on an existing Intellectual Property (IP).

In their vision statement, Ubisoft Film & Television states that it wants to ‘bring Ubisoft’s award-winning games into new areas of entertainment and to create original stories set in the world, culture and community of gaming.’ This phrasing stuck with me, because it implies that Ubisoft has as much to gain from selling its existing IP than it does from selling the idea of creating video games. Commercially, it’s a smart move. In a saturated market, selling a product on its own merit is no longer enough—everything can be replaced with a cheaper version, and every new product is faster to produce, ship, and deliver than the last. To create true customer loyalty, brands need something more than a great product. As the success of the Marvel Cinematic Universe has taught corporations, exploiting existing IP through film and TV is the way forward, presenting new avenues for marketing and potentially endless spinoffs to generate profit.

This has not only paved the way for an era of remakes, spinoffs, and reboots, creating often bland and repetitive media, but also one where even original-sounding work exists as fodder to be exploited, as Keno wrote in her previous essay on Yesterday’s use of The Beatles’ IP. While Disney churns out yet another live action remake, and Universal follows suit, Mattel, fresh off the commercial and critical success of 2023’s Barbie, is set to expand its universe with a host of toy-related movies. With Mythic Quest, Ubisoft goes one step further than Mattel did. Where Barbie had a fictional Mattel CEO (played by Will Ferrell), Mythic Quest is set entirely on the premise of a fictional workplace. It sells the idea of the game industry, and by extension, the idea of Ubisoft’s own workplace. The gaming industry is so fun and the games are built with so much love, by people who are so passionate about their art form, that they do not seem to exist beyond the walls of their offices. And why would they? They have everything they need right here, in the open space planning of their workplace, where the kitchen is always stocked, and everyone is family.

While it is good and important to support the people making the art you love, Mythic Quest is ultimately not about them. The show isn’t about Ubisoft’s creative teams, their journeys, their intentions, or their aspirations. It is an abstracted, ideal vision of its workers, designed to maximise brand loyalty. Look at these lovable, goofy characters, it says, don’t you want to support them while they do what they love? It's an alluring fantasy, because fictional characters cannot have differing opinions the way human workers can, they cannot question authority, or quit, or worse… unionise. On this last point, it is interesting to observe how the show evolved in parallel to its industry’s unionisation efforts—UK video game workers unionised in 2019 with the Game Workers Unite (GWU), and most recently, at the 2025 Games Development Conference, Video Game Workers launched an industry wide, direct-join union with the Communications Workers of America. Mythic Quest does not tackle unionisation, and I don’t believe it exists solely to bust union efforts, but it is important to situate it in the wider context in which it was created, because it helps us better understand the motivations a corporation might have in selling its workplace through fiction. Being loyal and unquestioning of a fictional workplace is the first step to being loyal and unquestioning of a real one.

In their Barbie video, Broey Deschanel discusses the responses they received when they initially shared their intentions to discuss the film with their audience. One commenter noted their frustration with criticism of the Barbie movie, insisting that the movie should be acknowledged for its passion, care and attention to detail, rather than for being a product of Mattel. I get where this is coming from: we live in an environment that is increasingly hostile to artistic creation. Creative work is harder to fund and even harder to sustain, and the TV shows we love are constantly getting cancelled due to their 'unprofitability.' When art is so easily devalued it is easy to feel that any criticism of it is an attack on its existence. And if we only value things in proportion to their labour and monetary output, it can be seductive to defend art by highlighting just how much work went into it. My concern, however, is that the corporations behind these IP-driven properties are aware of this anxiety, and that they will increasingly start using cultural cachet and artistic labour as leverage against criticism of their commercial intent—until we have completely lost the capacity to be critical. Is Thor: Ragnarok still military propaganda if indie darling Taika Waititi directed it? Is Mufasa just another way for Disney to profit off its existing IP if it was made by Best Picture winner Barry Jenkins? Is it really that bad if one of the world’s largest video game companies commissions a show to strengthen its brand image if the team behind It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia is at the helm?

The failure to recognise corporate messaging in our media is something I have seen echoed in my research for this essay, reading comments after comments explaining why Mythic Quest could not possibly be Ubisoft propaganda. On Reddit, one user noted that the show was not propaganda but in fact a ‘scathing critic (sic) of Ubisoft’, because ‘everybody in the office is a terrible person, and Montreal [the game in-universe headquarters] are depicted as incompetent, greedy and stupid.' This shocked me as such poor media literacy: a show commissioned, funded, and promoted by a massive corporation can never be a scathing critique of it, no matter how unlikable the characters are, or how many self-aware jokes are thrown in the mix. As Broey Deschanel puts it in their essay: ‘If we’re past corporations trying to sell us stuff through art, we might as well just give up.’ I don’t want to give up. Mythic Quest was a good show to spend four seasons with, but there is a better, smarter, funnier, and more pertinent show within it that was stifled by corporate interests, and I believe this is the show we deserved to watch.

1 Mythic Quest’s title is no doubt a reference to the popular 1999 MMORPG EverQuest, distributed in Europe by Ubisoft.

2 I’d like to stress here, as a French person myself, that Ubisoft is very important to France. If you watched the 2024 Paris Olympics opening ceremony, you may have seen a masked character running and jumping across the city’s landmarks, and even riding the metro, a reference to one of Ubisoft’s most iconic game Assassin’s Creed.